by Gregory Shank*

One of the longest-serving Social Justice editorial board members has passed away. Julia Rosalind Schwendinger died at the age of 87 on October 17, 2013, in Hudson, Florida. The daughter of Russian immigrants Jacob and Lena Pliskin Siegel, she was born on September 3, 1926, and grew up on 84th Drive in Jamaica and in the Rockaway Beach area of the New York City borough of Queens. Julia and her husband of nearly 68 years, Herman “Hi” Schwendinger, were inseparable. They helped each other get through college in the years just after World War II by teaching square dancing to teenagers. Julia played the piano and Hi called the moves. A fellow folk dancer and friend, the late Irwin Silber, could be found at Saturday night square dances at Furriers Union Hall on New York City’s West 28th Street in the late 1940s. The People’s Songs/Artists movement spearheaded by Silber and Pete Seeger promoted the music of the American labor movement and raised funds for movement activities. Folksay and People’s Songs, which were affiliated with the American Youth for Democracy, sponsored square dances featuring politically themed calls and folk plays; its publication Sing Out highlighted storied American music treasures such as Woodie Guthrie, who deeply influenced the young Bob Dylan. In 1952, the House Un-American Activities Committee’s inquisitors deemed this music-making, dancing, and theater to be communist-inspired efforts to “control youth groups.”

Julia earned a bachelor’s degree in sociology at Queen’s College (1947), a master’s degree in social work at Columbia University (1950), and a doctorate in the School of Criminology at the University of California, Berkeley (1975). Her dissertation, entitled The Rape Victim and the Criminal Justice System, was intimately connected with her work in founding the first anti-rape group in the United States, which arguably became the model for such work internationally. Julia and Hi became a formidable presence in the fledgling radical criminology movement of the 1970s, as well as in the struggle for women’s rights, and continued to make meaningful contributions throughout the following decades. Julia accomplished this despite a long-term struggle with life-threatening cancer, which was first manifested in the early 1970s.

Julia was consistently an activist-scholar. She opposed the Vietnam War, supported the Civil Rights Movement, and, most recently, the Occupy Movement. In her first social work position, she worked with children and teens in a poor high-crime community. Given Hi’s youthful involvement in gang activity in New York City and his early fieldwork with street gangs as a social group worker, their interests meshed well. That experience and their firsthand knowledge was invaluable in their seminal ethnographic work on adolescent social types and delinquent gangs, which Julia and Hi began while associated with the sociology department at UCLA in the early 1960s. Her community orientation and organizing skills were also apparent in the founding of the Bay Area Women Against Rape (BAWAR) in 1971, along with Oleta “Lee” Abrams. In her Rape and Inequality, Julia described the group as a tiny handful of women composed of political activists and militant feminists who saw themselves as advocates of rape victims in the established institutions. This trendsetting victim-assistance program combined scholarship with community activism, an integral element of the journal Crime and Social Justice (our inaugural title in 1974). Julia was the journal’s book review editor in the first edition and was the lead author of the landmark article “Rape Myths: In Legal, Theoretical, and Everyday Practice.” She was a meticulous editor and polished all of their coauthored writings before they could be considered ready.

Beyond her numerous academic accolades, Julia was a kind and caring mentor. Maggie Bollenbacher, an early BAWAR member, spoke of Julia’s humanity and skillfulness as a leader: “She was sharp and witty, warmhearted, and committed to her family and friends. When I joined BAWAR I was fresh out of college in Minnesota and my eyes were beginning to open to the ways of the world. My associations with Julia Schwendinger and Suzie Dod made me a much wiser and fuller person. Julia strongly influenced me through her intellectual contributions to group discussions at BAWAR meetings in the early 1970s. She offered us a better understanding of a rapist’s mentality within the context of our society. Certainly, our focus was on helping the victims and getting the work done, but Julia and women like Suzie always sought to understand why this harmful behavior was occurring in the first place. Julia pointed to the psychosocial and economic factors underlying violent behavior in America and the ways in which the criminal justice system aggravated the harm already done.” Before her death, Suzie Dod Thomas fondly recalled the inclusive spirit of the period. Although Suzie was working as a secretary at the time, Julia encouraged her to join BAWAR as well as the radical criminology movement, including participation in Crime and Social Justice. Julia and Tommie Hannigan used their BAWAR funding contacts to obtain seed money for the initial editions of the journal.

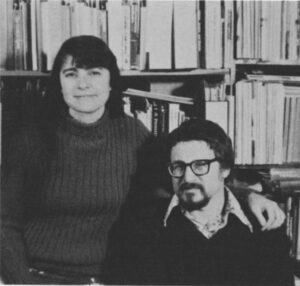

During the journal’s formative period, Julia and Hi traveled widely, visiting like-minded scholars and practitioners in England, Germany, Austria, the Netherlands, France, and Italy. Many boisterous journal meetings and events such as the launching of The Iron Fist and the Velvet Glove took place in the Schwendinger’s home on Vincente Avenue in North Berkeley. Julia cut a striking figure, her long black hair framing her attractive face and ready smile. Her low, smooth voice and self-confidence had a calming influence, while her diminutive mother Lena radiated warmth and a sense of purpose with her ever-present petitions in need of signatures. But make no mistake: Julia was a tough, eloquent, and unapologetic Marxist. She typified the unqualified nightmare then consuming the Berkeley administration and the forces of reaction consolidating in Sacramento under the mantel of Ronald Reagan.

And so the magnificent experiment underway in Berkeley’s School of Criminology was decisively dismantled and most of the core critical faculty and students associated with the journal were sent packing. The noose tightened nationally to eliminate progressive faculty and prevent graduate students radicalized in the 1960s and 1970s from gaining a professional foothold in the academy. In the short term, Julia found work as a private investigator and consultant, providing presentencing reports on offenders for defense attorneys and judges. She was a parole commissioner and director of the Women’s Resource Center for San Francisco Jails, in association with the late Richard Hongisto. In the period Julia described as exile, she taught sociology, criminology, and criminal justice at Vassar, the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, SUNY (New Paltz), and finally at the University of South Florida. She worked briefly at UC Berkeley’s Institute for the Study of Social Change and was an exchange scholar with Hi at universities in Berlin, St. Petersburg, Moscow, and central Asia.

Based on the latter experiences, Hi and Julia wrote a 1993 firsthand account in Humanity and Society entitled “The Crises of Soviet Legitimacy,” in which they examined the paradoxes and changing class character of Soviet society just before the collapse. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Julia and Hi regularly published articles in this journal on rape, delinquency, prison living standards, and social class and the definition of crime. Working closely with Tony Platt and Paul Takagi, Julia lined up Friendly Fascism author Bertram Gross to participate in an international discussion centered on his essay, “Some Anticrime Proposals for Progressives” (Crime and Social Justice 17, Spring-Summer 1982). Their most recent books are a history of the Berkeley School of Criminology and Big Brother, which analyzes the expansion of surveillance technology in the United States and the repression of left-wing ideas and policies.

Julia will be sorely missed by the many whose lives she touched and especially by Hi and their children, Leni and Joseph.

* Gregory Shank is the Co-Managing Editor of Social Justice and a long-term Bay Area resident.