by Margaret Randall*

International Women’s Day, March 8th, is my favorite holiday. Every year I write a brief tribute—to remind my friends and also myself how much women everywhere give to resist oppression and sustain life. Usually I’ve focused on a group of women whose ordinary heroism was particularly noteworthy since the previous March. South African or Palestinian women. The desperate women of Syria and Sudan. Women in prison. Women right here in the United States, who face every sort of degradation. This year I want to honor our scribes, the women in so many different parts of the world and throughout history who, often against incredible odds, have told our stories and kept history alive. Not just women’s history, everyone’s. I want to narrow my focus to women who tell our stories—in dozens of different ways. If our stories are not preserved and told, we cannot know who we are. And if we do not know who we are, we will never become who we want to be: healthy, creative, brilliant and compassionate peace-making contributors to society.

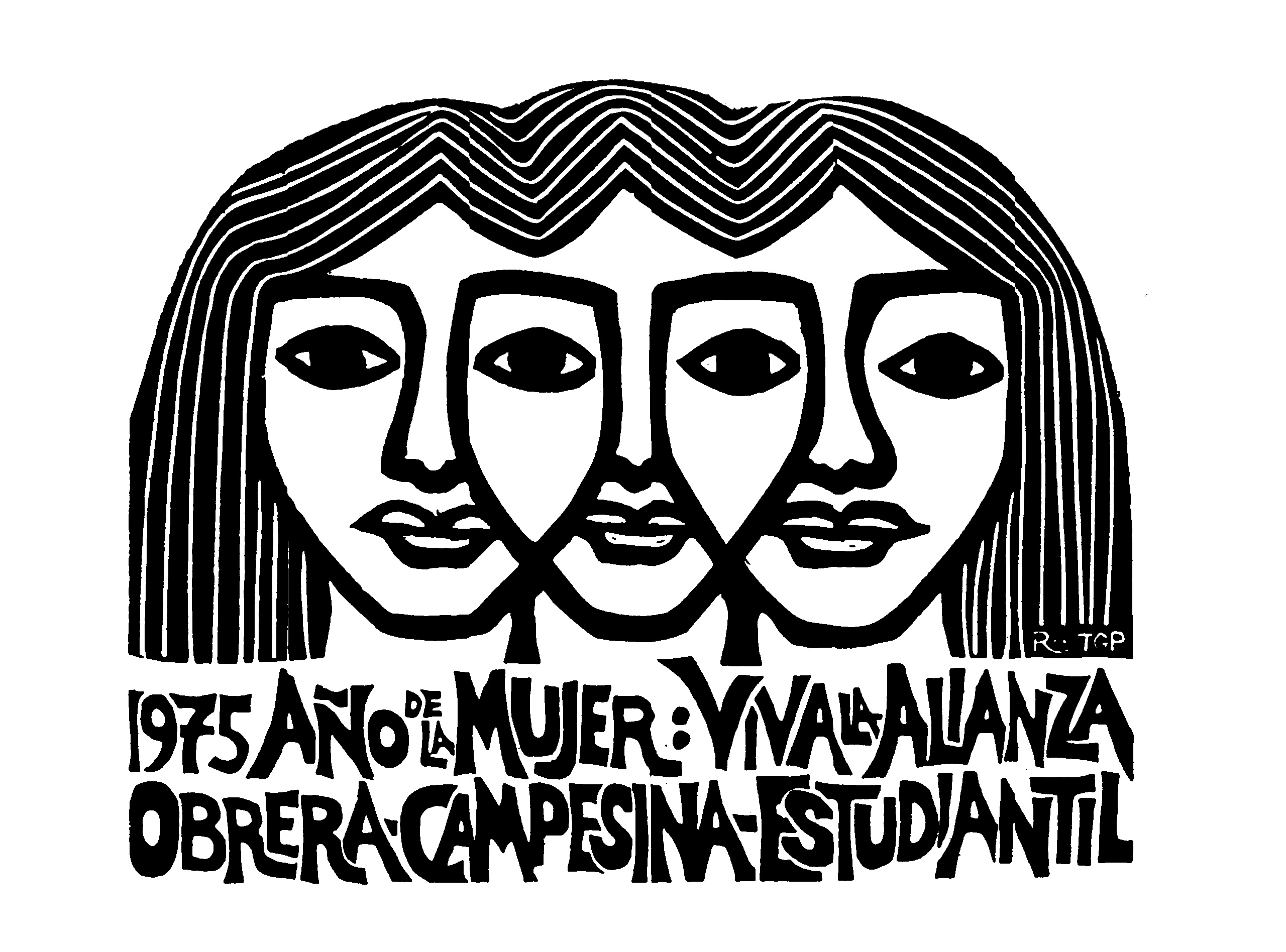

Women often tell our stories and the stories of others through art. Guatemalan women embroider them into the intricate huipiles (blouses) indigenous to each of the villages in that country, where individual and collective histories can be read in brilliantly colored strips of flowers, birds and other symbols denoting origin, civil status, number of children and more. Closer to home, Navajo women weave them into rugs, and many Pueblo women fashion them into pots or storyteller dolls. Women were prominent in sewing squares in what would become the great AIDS quilt of the 1980s, finally so large that it could not be unfolded in its entirety on the Washington mall. The HIV/AIDs pandemic devastated communities but gave women the opportunity of bringing traditional quilting skills into an arena of commemoration and resistance. Some of the greatest poetry of the 20th and 21st century has been written by women; in the US names such as Hilda Doolittle (HD), Muriel Rukeyser, Meridel LeSueur, Mary Oliver, Adrienne Rich, Audre Lorde, Joy Harjo, and Sandra Cisneros are only a few in a very long list. All these women artists, well known or anonymous, have told pieces of our story. Their words exhilarate and empower us. They give us literature and recovered memory.

Women often tell our stories from situations of terror and confinement. Recent decades have seen women here and throughout the world speaking out about incest, rape, and battery, telling our stories despite the threats of those who would silence us. Each woman’s story makes many others possible. And all our stories together have changed the way society views domestic violence.

After Chile’s 1973 fascist coup, some three thousand men and women were disappeared or tortured to death. The more fortunate were forced into exile or filled the dictatorship’s prisons and concentration camps. It was in those prisons and camps that women began producing arpilleras, applique squares made with bits of cloth and small lengths of thread. These scenes, which often also incorporated words, told picture stories of repression and resilience, a universal desire for peace and security. In Vietnam, during the last years of the American War, women prisoners wove delicate baskets from strands of their own long hair. Those baskets, too, told empowering stories of resistance.

Just touching on a few examples of the deeply creative ways women have found to break the silences imposed upon us by centuries of gender discrimination would require a piece much longer than this one. So I will end with a dramatic story in which several generations of women have contributed to telling a history never meant to be told. In South America, during the 1970s and ‘80s, what we called the Dirty Wars took place in Chile, Argentina, and Uruguay. Brutal dictatorship attacked whole generations of freedom fighters and ordinary citizens, many of them women, who were struggling for a minimal rule of law. Young couples were often captured together. Sometimes the woman was pregnant. The men would most often be tortured and killed right away, but the pregnant women were kept alive until they gave birth. Thus began a heinous chain of events, in which the infants of revolutionaries were handed over to childless couples among the fascist ranks. Their mothers, newly delivered, were then murdered as well.

For decades a group of women who call themselves The Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo have marched weekly in Buenos Aires’ civic square, carrying photographs of their disappeared children and demanding to know where their bodies are buried. The Mothers eventually became the Grandmothers. As the stolen children grew up in the homes of those consciously or unconsciously responsible for their parents’ deaths, a new technology for determining genetic identity became available: DNA. A group of scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) brought the technology to Argentina and offered it to the Mothers, who over time developed a genetic database. Through the next couple of decades, some of the stolen children—now in their thirties—have had occasion to wonder about their origins. Slowly, in some cases hesitatingly, they have approached the Mothers or the Mothers have approached them. To date, more than one hundred stolen children have been reunited with their grandparents.

On this International Women’s Day I want to pay tribute to the Mothers who have become Grandmothers, refusing to give up on telling the stories of children who were taken from them so brutally, never to be seen again. And I want to pay tribute to those young revolutionary women, murdered after giving birth, who continue to tell their stories, with their own DNA, from beyond their unknown graves. They write these stories not with public speeches or poetic words, not with human hair or scraps of cloth, but with their genetic material, the remnants of their own bodies—and the help of a science focused on life rather than death.

Whatever it takes. And as long as it takes.

* Margaret Randall (mrandall36@gmail.com )is a feminist poet, writer, photographer, and social activist. The most recent of her more than 80 published books is Che on My Mind (Duke University Press, 2013).