by Maartje van der Woude*

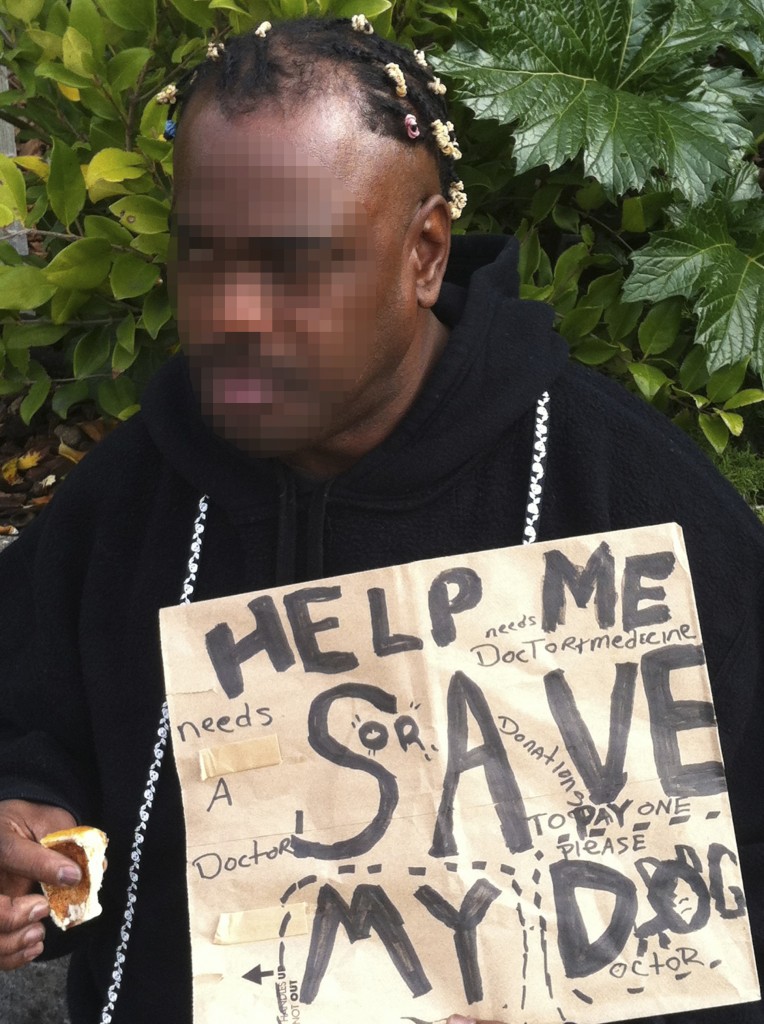

“Pietprotest” by Constablequackers – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

I vividly remember how excited I was on December 5,1985—the national Dutch holiday of Saint Nicholas (Sinterklaas)—when as a five-year-old girl I painted my white face black and my lips bright red and put on black tights, black gloves, and brightly colored clothes, topped by a huge Afro wig. I was ready to celebrate this annual pre-Christmas holiday with thousands of other Black Petes in the schools and on the streets. Dressing up in blackface in public not only was seen as “normal” but was also encouraged by the authorities.

It wasn’t until the year 2000, when I started to spend more time abroad, particularly studying and going to conferences in the United States and the United Kingdom, that I began to have second thoughts about this seemingly innocent tradition. And it wasn’t until 2013, when activists in the Netherlands began to raise questions about the racist origins of the holiday, that I started to seriously think about my own responsibility to address this issue in university classrooms and in my writings.

Though the history of the Saint Nicholas celebration in the Netherlands dates back to the Middle Ages, the character of Black Pete was not introduced into these festivities until 1850, when a teacher, Jan Schenkman, published “Saint Nicholas and His Servant.” Schenkman created the character of Black Pete as Nicholas’s sidekick, helping the old white Saint to deliver presents to children. Subsequently, illustrators and writers interpreted Pete as an African slave, a servile figure dressed as a page, with curly hair, big lips, and large golden earrings. By the 20th century, Black Pete spoke broken Dutch in an exaggerated Surinamese accent, parodying his homeland, a Dutch colony until 1975.

Until a couple of years ago, there was hardly any public dissent about the incorporation of minstrelsy into a national holiday. A small group that organized to protest Black Pete in 2010 had a big breakthrough in 2013 when the United Nations High Commission for Human Rights sent a letter to the Dutch government asserting that Black Pete perpetuated an image of people of African descent as second-class citizens and constituted a “living trace of past slavery.” In its reply, the government of the Netherlands defended the holiday as a traditional children’s festival and reminded the Commission that there are formal procedures in the Netherlands through which people may raise complaints about discrimination.

Activists continued to organize at the local level. In the fall of 2013, a small group of organizations, led by Curaҫao-born performance artist Quinsy Gario, filed a series of complaints against the city of Amsterdam, demanding a banning of the November 2013 parade welcoming Saint Nicholas and his Black Petes. The district court of Amsterdam ruled in favor of the petitioners, requiring the city to take into account the racial implications of the ceremony before issuing a permit for the parade. Referring to a decision by the European Court of Human Rights (Aksu v. Turkey), the court ruled that negative stereotyping of a social group can have a deep impact on the group’s sense of identity, self-worth, and self-confidence. In response, the mayor of Amsterdam filed an appeal against the verdict with the administrative court of appeals, the Council of State.

On November 12th, the Council of State overturned the District Court’s decision on technical grounds, claiming that the question was out of its purview and that the mayor doesn’t have the power to ban people from dressing up as Black Pete in public. The official 2014 Saint Nicholas parade took place five days after the ruling in the city of Gouda. Despite the presence of yellow and light-brown Petes—colors referring to yellow Gouda cheese and the typical Dutch cookie, the stroopwafel—Black Petes were in attendance once again, albeit this time with less ostentatious golden earrings. In the name of security, armed Petes in bulletproof vests accompanied the Saint. During the festivities, about 90 activists protesting against Black Pete got arrested for “causing public nuisance.” Protests also took place in Amsterdam.

The Black Pete debate coincided with a number of well-publicized events in 2013 to mark the 150th anniversary of the abolition of the slave trade. Local and national exhibitions, seminars and workshops, and televised programs drew attention to the prominent role of the Netherlands in the buying and selling of some 600,000 Africans, shipped from its fortresses in what is now known as Ghana. Throughout the year, Black community and cultural organizations were active in remembering the history of slavery and its legacies through a variety of local events, culminating in the creation of the National Slavery Monument in Oosterpark in Amsterdam, the Keti Koti festival, and other forms of commemoration. The anniversary also led to the creation of the Amsterdam Black Heritage Tour, which sheds light on the historic impact of the transatlantic trade and plantation system on the economic development of the Netherlands and the riches of the Amsterdam Canal District.

The events marking the abolition of the slave trade and the protests against Black Pete created for the first time a national conversation about the country’s complicity in the slave trade, the role of slavery in the rise of the Netherlands as a global economic power, and the place of race and racism in contemporary Dutch society.

In 2014 discussions on racial and ethnic disparities in Dutch society continued, transcending the Black Pete case. The silence around these matters was finally broken. This is most prominently illustrated by current debates on ethnic profiling by the Dutch police in bigger cities and the increase of organized protest groups.

The discussion about race has generated fierce political and public debate. For some on the Right (notably the Party for Freedom), this is an opportunity to exploit anxieties about a prosperous and safe Netherlands losing its national identity and folk culture, a fear that is undoubtedly fueled by globalization, migration, and the notion that the European Union is gradually supplanting the European nation state (Van der Woude & Van Berlo 2015). In this sense, what is happening in my country is similar to political trends throughout Europe.

The topic of race in the Netherlands, for too long silenced in classrooms and public squares, will no longer be ignored. Thanks to courageous grassroots activists and some outspoken politicians and professionals, the relationship between the country’s colonial past and racial-ethnic inequalities today has become a matter for discussion and action. In a recent issue of one of the national newspapers, Dutch universities and academics were explicitly accused of remaining silent in the debates concerning the Black Pete protests.

I do not intend to remain silent. Through writing for fellow academics and for the larger public, as well as actively engaging my students, I will do my part to raise awareness about this matter of national significance.

References

Leun J.P. van der & Woude M.A.H. van der (2011), Ethnic profiling in the Netherlands? A reflection on expanding preventive powers, ethnic profiling and a changing social and political context, Policing and Society 21(4): 444–55.

Platt, T. (2014) Slavery and Genocide: State of Remembrance? Discover Society, March 4, 2014.

UN Human Rights, “Statement by the United Nations’ Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent, on the conclusion of its official visit to the Kingdom of the Netherlands, June 26–July 4, 2014.”

Woude, M.A.H. van der & Berlo, P. van (2015) Crimmigration at the Internal Borders of Europe: The Schengen Governance Package, Utrecht Law Review (forthcoming).

*Maartje van der Woude (email: m.a.h.vanderwoude@law.leidenuniv.nl) is an Associate Professor of Criminal Law at the Institute for Criminal Law & Criminology at Leiden Law School, the Netherlands and a deputy judge at the Criminal Court of the District Noord-Holland. The author would like to thank Cecilia O’Leary and Tony Platt for their feedback on earlier versions of this blog.