by Clifford Welch*

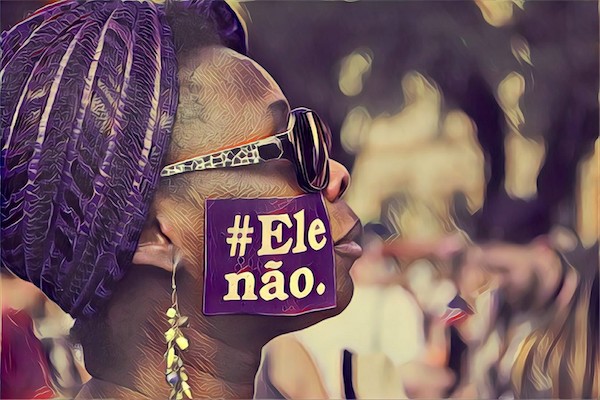

Image: Demonstration against presidential candidate Jair Bolsonaro in Porto Alegre, Brazil. September 29, 2018. By Caco Argemi CPERS / Sindicato. Source: Flickr. CC BY-SA 2.0. Edited.

The front-runner in Brazil’s upcoming presidential election refuses to debate his opponent. He prefers to generate and reproduce disinformation about his opponent without ever issuing an apology or correction. Sounds familiar? In fact, front-runner Jair Bolsonaro looks upon Donald Trump as his mentor, and Trump’s former campaign manager, Steve Bannon, has been an unofficial advisor to Bolsonaro, who sees Bannon as part of his “popular-nationalist” movement.

Unlike Trump in 2016, Bolsonaro’s candidacy is favored by the embarrassing recent record of his opponent’s party, the Workers’ Party (PT). Corruption charges have put several party leaders behind bars. The PT has repeatedly denied the charges and defended a claim of being more honest than any other political party in Brazil. It won three presidential elections with this argument and up until a month before the first-round election, polls showed the PT’s founding light, Luís Ignacio Lula da Silva, as the front-runner, even though he was in jail. With Lula definitively barred from running by the courts, the PT put forward Fernando Haddad, a former mayor of São Paulo and university professor. As his running mate, they selected Manuela D’Ávila, a popular congresswoman from the Communist Party of Brazil (PCdoB), both publicly endorsed by Lula just before he was jailed. Whereas much of the evidence against the party is credible, the current PT candidates represent a new generation of leaders untouched by scandal.

In the first round of elections, held on October 7, the voters’ top two choices were Bolsonaro, with 46 percent of the vote, and Haddad, with 29 percent of the vote. This election eliminated another 11 candidates and established Bolsonaro and Haddad as the two finalists. The final round of the process is scheduled for October 28.

Reliable polls show Bolsonaro winning with 58 percent of the vote. Many worry that a country that struggled so hard to overcome military rule is about to vote for military rule. In fact, Bolsonaro rose to rank during the later stages of the dictatorship. His vice-presidential running mate is a retired Army general, and another general is coordinating the work of some 30 study groups developing policies for governing the country. Many additional military officials run each of these groups. Military men are capable of respecting the law, but leading officials in Bolsonaro’s camp express their disdain for laws and regulations, like those controlling deforestation and protecting minorities. Just about four years ago, the country passed through a period of reckoning, involving truth commissions at every level—from local institutions to the federal government—analyzing the dictatorship and its crimes on the 50th anniversary of the 1964 coup d’etat. The current resurgence of the military in politics seems in part to be a reaction, as they have stridently denied any wrongdoing and oppose reparations for violating the human rights of their victims.

Bolsonaro, like Trump, shows little respect for democracy. During the campaign, he refused to participate in debates and proudly rejected negotiation with political leaders and parties, accepting endorsements while declaiming deals. After the first round, he accused the electoral system of fraud and said that he will not accept electoral results if he loses the final vote. In a radio interview, he reinforced his rejection of the debates. His handlers seem intent on using an assassination attempt on the candidate in September to keep him cloistered while they run his campaign through social media, where “fake news” has included absurd allegations against Haddad, such as support for incest and sex (rather than sex education) among minors.

In the meantime, Haddad and the PT are anxiously planning, negotiating, and campaigning to accumulate at least nine more points to win. He has released a plan for his government, including solutions for Brazil’s devastating economic crisis. Haddad is reaching out to Protestants and Catholics in order to counter the support Bolsonaro has received from evangelicals. (Evangelical leaders see in the thrice-divorced Bolsonaro a defense of “family values,” defined as male dominance, opposition to reproductive rights, and intolerance for the LGBTQ community.) Haddad has sought the endorsement of losing presidential candidates and incorporated the third-place candidate in his proposal for government ministers. However, many politicians and parties have expressed neutrality. Given Bolsonaro’s lead, a neutral position is actually an endorsement for the former Army captain.

With Bolsonaro’s campaign oriented by Paulo Geudes, a “Chicago boy” neoliberal trained by Milton Freidman, and staffed by military officials, the business class supports him. If elected, Brazilians can expect a reactionary transformation similar to that undertaken by Chilean Gen. Augusto Pinochet in the 1970s, whose dictatorship imposed draconian structural adjustments on Chile. These included huge cutbacks to education and health care as well as privatization and selling off of public universities and hospitals. Bolsonaro has proposed something like a flat tax that actually raises taxes abruptly on all but the poorest wage earners. Among the demands of the agribusiness sector is the further relaxation of controls on Amazon rainforest deforestation. The “lungs of the world,” as the Amazon is called, could soon be lost. Bolsonaro has also said that he will classify rural social movements as terrorist organizations. His plan for governing has not yet been released, but his statements already make clear his intention to ignore constitutional responsibilities, like agrarian reform.

Bolsonaro has used Manuela’s party affiliation to redbait Haddad and warn of Brazil becoming another Venezuela. Haddad’s poor showing in São Paulo during the first round demonstrated the ticket’s limited appeal among the middle and ruling classes. These were the groups that gave their full support to the 1964 coup. Bolsonaro’s success at mobilizing the support of poor, working-class, and Afro-descendant voters, including women, is what has surprised analysts on the left. Certainly, contradictory aspirational outlooks, especially in the context of a difficult and long recession, play an important role. Bolsonaro’s propaganda includes numerous testimonials from supposed supporters who are Black and female.

In the face of Bolsonaro’s popularity, the PT will have to struggle relentlessly to retake the presidency. It is clear that the Bolsonaro campaign is oriented by hatred. The PT would do well to adopt an anti-hatred stance. It could be geared to undermine Bolsonaro, while it indirectly provokes people to reconsider their dismay with the PT.

In appealing for a politics oriented by love rather than hatred, the PT has to emphasize its outsider status and thus the change its victory will represent. The recent elections, as well as support for Bolsonaro, demonstrate the voters’ intense hope for change. Bolsonaro and his party are new to the national political scene. The parties currently in power lost big in the election, despite their advocacy of neoliberal policies very similar to those of Bolsonaro. Their presidential candidates received little more than 5 percent of the vote.

Finally, Haddad and Manuela need to emphasize how they symbolize not the restoration of Lula—the current jingle is “Happy again” with the PT—but rather the renovation of the party. In other words, they have to make people believe in the dream the PT represented to people when Lula was inaugurated in 2003 and tens of thousands of people gathered in the capital to cry with joy. As new but politically experienced and savvy politicians, Haddad and Manuela give the party a chance to reach the presidency and nurture the growth and prosperity of a socially just Brazil. The alternative, Bolsonaro’s victory, will instead bring division, repression, and more capital accumulation for the one percent who already receive a third of Brazil’s income, making the county the world’s most unequal in income distribution.

Against hate, for love, change and renewal!

• • •

*Clifford Welch is a former San Francisco longshoreman, ranchhand, reporter, and cofounder of the National Writers Union. He teaches contemporary Brazilian history at the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP). A previous version of this piece has been published by the Latin American Perspectives blog (here).