by Tony Platt*

Anniversaries provide many opportunities for revisionist and wishful thinking about the past. The 50th anniversary of the Kerner Report is no exception.

The new mythology remakes the Kerner Commission as a bastion of liberal democracy and enlightened social science, betrayed by a political system, especially President Johnson, that succumbed to political pressures from the Right. In reality, the Commission itself was marked by internal contradictions and contributed to the repressive policies that brought Richard Nixon to power in 1968.

The Kerner Report, recalls former Senator Fred Harris, the one surviving commissioner, “recommended ‘massive and sustained’ investments in jobs and education to reduce poverty, inequality and racial injustice.” Conveniently forgotten are the forty pages of recommendations for improving the riot control capacities of police, National Guard, and Army.

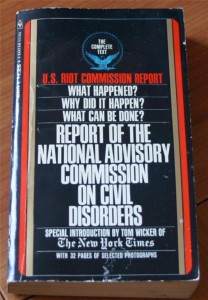

Following several years of urban revolts, in July 1967 Lyndon Johnson appointed the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (popularly known as the Kerner Commission after its chairman Otto Kerner) that worked at a furious pace and published a memorable report a few months later on March 1st, 1968.

Unlike previous official inquiries into civil disorders, the Kerner Commission was the first federally funded, national, and Presidential-level inquiry into US race relations. The size and scope of its final report was comparable to Gunnar Myrdal’s An American Dilemma, published twenty-four years earlier. The Kerner Report provided seemingly unassailable moral authority for the proposition that “our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white – separate and unequal…. What white Americans have never fully understood – but what the Negro can never forget – is that white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it.”

This unprecedented statement by a government commission was followed by proposals to end discrimination in jobs, education, and housing; expand the welfare state; make policing more responsive to African American communities; provide six million low-income families with public housing; and eliminate institutionalized segregation. In other words, complete the promise of the New Deal.

Fifty years later, the promise is still unfulfilled. Public schools and public housing remain hyper-segregated in many parts of the country; the rate of poverty remains about the same, while the gap between rich and poor has increased; and mass incarceration became the new welfare.

In the search for explanations about how an incipient social democracy was derailed, there is a tendency today to reify the Kerner Commission as a united liberal front trying to hold the line against Johnson’s opportunism and what would become neo-conservatism.

The Commission itself was divided and tried to juggle reform and repression. It was opposed to the mobilization of tanks and machine guns in the immediate response by government forces to “civil disorders” on the grounds that “the indiscriminate and excessive use of force” was counter-productive. Instead, the Commission advocated more sophisticated and diversified forms of counter-insurgency, including the establishment of “intelligence systems” and “rumor collection centers,” the training of special police units to infiltrate Black communities, the preparation of police for “riot control,” the development of a variety of “non-lethal chemical agents” in order to achieve “temporary neutralization of a mob,” the increase of “riot control training” for the National Guard, and the strengthening of the Army’s ability to “control civil disorders,” including the use of “psychological techniques to ventilate hostility.”

In sum, concluded the Kerner Commission, riot control required “large numbers of disciplined personnel, comparable to soldiers in a military unit, organized and trained to work as members of a team under a highly unified command control system.”

The second myth about the Kerner Report is that social scientists writing about race in the late 1960s were a unified bloc whose politics ranged from left liberal to radical. In fact, academics, including the commission’s consultants and researchers, were deeply divided. White men administered the Commission’s internal functions, with Black staffers primarily sent out to do interviews in African American communities. “The whole thing was a racist operation,” said a field investigator.

According to Andy Kopkind’s contemporaneous critique, the contributions of leftist intellectuals were sidelined. The White House vetoed Herbert Gans’ involvement because of his protest against the Vietnam War and the Commission’s technocrats made sure that bold ideas in “The Harvest of American Racism,” a report written by progressive sociologists, were “popped down a memory hole.”

Instead, intellectuals in a private war research company, the Institute for Defense Analysis, shaped the Commission’s mix of soft and hard techniques of social control, a strategy endorsed by many leading social scientists, such as Neil Smelser and Morris Janowitz, and later by James Q. Wilson and other academics for law and order who articulated the punitive turn of the 1980s.

The Kerner Report remains an important statement about the lost opportunity of social democracy. But it is also testimony to the combination of benevolent rhetoric and repressive interventionism that characterized Cold War liberalism, and prefigured the rise of neo-liberalism. Johnson was not the only one who, in the words of Fred Harris, “distanced himself from the ‘two societies’ warning.” So did the Kerner Commission.

• • •

Sources

Fred Harris and Alan Curtis, “The Unmet Promise of Equality,” New York Times (March 1, 2018).

Elizabeth Hinton, From The War on Poverty to The War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America (Harvard University Press, 2016).

Morris Janowitz, “Social Control of Escalated Riots,” University of Chicago Center for Policy Study (1968).

Andrew Kopkind, “White on Black: The Riot Commission and The Rhetoric of Reform,” in Tony Platt, ed., The Politics of Riot Commissions, 1917-1970 (Macmillan, 1971).

Nicole Lewis, “The Kerner Omission,” The Marshall Project (March 1, 2018).

National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, Report, introduction by Tom Wicker (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1968).

• • •

* Tony Platt is a member of the editorial board of Social Justice, and editor of The Politics of Riot Commissions, 1917-1970 (Macmillan, 1971). His latest book, Beyond These Walls: Rethinking Crime and Punishment in the United States will be published by St. Martin’s Press in January 2019.